- 定價200.00元

-

8

折優惠:HK$160

|

|

|

|

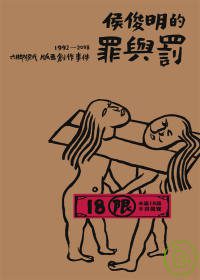

侯俊明的罪與罰:1992-2008六腳侯氏版畫創作事件

|

|

沒有庫存

訂購需時10-14天

|

|

|

|

|

|

9789867009524 | |

|

|

|

侯俊明 | |

|

|

|

田園城市 | |

|

|

|

2009年1月10日

| |

|

|

|

227.00 元

| |

|

|

|

HK$ 192.95

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

詳

細

資

料

|

* 規格:平裝 / 366頁 / 8k / 限制級 / 全彩 / 初版

* 出版地:台灣

|

|

分

類

|

[ 尚未分類 ] |

同

類

書

推

薦

|

|

|

內

容

簡

介

|

《侯俊明的罪與罰》呈現了一位誠實且真實的藝術家,這十六年來,一貫卻始終獨特鮮明的創作。

1963年出生於嘉義六腳鄉下,1982年以榜首成績進入國立藝術學院(今國立台北藝術大學)第一屆美術系就讀。參與不下數十場個展與聯展發表,也曾在香港、釜山、東京、威尼斯、柏林、紐約、哥本哈根、雪梨等地留下展出足跡。 從成年到中年,尾隨著八○年代和九○年代台灣的一路起伏,經歷著所有曾經在這塊土地上發生的事,同時在這些大小事件裡走過自己青年和壯年的人生故事。 二十九歲那年發表第一套版畫作品「極樂圖懺」,至今已創作了十套大型版畫作品和數十件單張版畫作品。1992年,反映自身現狀和處理生命困境的「極樂圖懺」;1993年,誕生於甫自戒嚴氛圍中解放出來、過往禁忌得以被討論的社會,並援引中國傳統神話故事而創作的「搜神記」;1995年,深受新婚生活影響的「四季春宮」;1996年,將年少時期就已隱然產生的女性主義憂懼發展成為「新樂園」,同時也因重新回到外在資訊大量爆炸的都會,得以創作「樂園?罪人」;1997年香港回歸前夕的短暫旅居,以同文同種卻外來的身分切入高度西化同時苦難仍存的百年殖民地,交出三件一套的「香港罪與罰」;1999年的「上帝恨你」既涉及自身的混亂,也揉合了對民間宗教「地獄圖」和鄉間電線桿警示標語那勸善為名、實則包容暴力的反思;而走過第一段婚姻、九二一大地震和世紀之交的集體慌亂後,於2006年發表「枕邊記」此一作品;進入2007年,藝術市場和中國那大國崛起式的炙燄燃燒則全部反映在「堀之龍」「翔之鳳」兩幅大型作品中;最新的「侯氏八傳」和「圳鳴四十七自述」則以自傳和自畫像的形式,回頭檢視過往生命階段的大起大落。 《侯俊明的罪與罰》呈現了一位誠實且真實的藝術家,這十六年來,一貫卻始終獨特鮮明的創作。

作者簡介

侯俊明

一九六三年出生於台灣嘉義縣六腳鄉,貫以「六腳侯氏」署名,畢業於國立藝術學院(現改制為國立台北藝術大學)美術系第一屆榜首。九○年代以裝置、版畫形式進行創作,大膽挑戰禁忌、富儀式性,作品恆常與當下台灣政治環境和社會現況有密切關聯。曾受邀「威尼斯雙年展」等國際展。近年創作轉向心靈探索的隨手畫和自由書寫。 著有《搜神記》、《三十六歲求愛遺書》、《榖雨?不倫》、《鏡之戒》

|

|

目

錄

|

8 【論】混沌的造型化/淺井俊裕

12 【序】幸運兒的墓誌銘/侯俊明

16 【引】1990-1991年劇場經驗對侯俊明創作的影響/陳富珍

27 1992 極樂圖懺

29 環境事件

32 創作自述

34 與侯俊明的版畫對話/簡丹

36 極樂圖懺圖版

53 1992 戰神、白馬郎君.1993搜神記

55 環境事件

58 創作自述

60 與侯俊明的版畫對話/簡丹

62 白馬郎君.戰神圖版

66 搜神記圖版

105 1995 四季春宮

112 環境事件

110 創作自述

107 與侯俊明的版畫對話/簡丹

114 四季春宮圖版

123 1996 新樂園

125 環境事件

132 新樂園圖版

128 創作自述

130 與侯俊明的版畫對話/簡丹

132 新樂園圖版

147 1996 樂園.罪人

149 環境事件

152 創作自述

154 與侯俊明的版畫對話/簡丹

156 樂園.罪人圖版

164 人圖版

167 1996 香港罪與罰.1997 盧亭

169 環境事件

172 創作自述

174 與侯俊明的版畫對話/簡丹

176 香港罪與罰圖版

182 盧亭圖版

185 1999 上帝恨你

187 環境事件

190 創作自述

192 與侯俊明的版畫對話/簡丹

194 上帝恨你圖版

209 2006 枕邊記〈大〉.枕邊記〈小〉

218 環境事件

216 創作自述

211 與侯俊明的版畫對話/簡丹

220 枕邊記〈大〉圖版

236 枕邊記〈小〉圖版

281 2007 堀之龍?翔之鳳

283 環境事件

290 堀之龍.翔之鳳圖版

299 2007 侯氏八傳.圳鳴四十七自述

301 環境事件

310 侯氏八傳圖版

306 創作自述

308 與侯俊明的版畫對話/簡丹

326 圳鳴四十七自述圖版

340 【附錄一】六腳侯氏.侯俊明創作年表

348 【附錄二】侯俊明參與的劇場活動與版畫創作的關係

353 【附錄三】1982~2008年台灣社會重要事件與侯俊明創作關聯表

|

|

序

|

序

幸運兒的墓誌銘文 / 侯俊明

可能是因為戒斷的關係吧,我最近常常開車途中就會熱淚盈眶的想哭泣。所以也就常常就把車子停在路邊,讓自己可以哭出來。飲泣也好,嚎哭也好,即使只是靜靜的流下眼淚,就讓眼淚流花了臉、浸濕衣衫吧。

其實我知道,不完全是因為戒斷,而是我的身心再一次的在經歷著生離死別的悲傷。我正站在生命的另一個轉捩點上。

如果要我此刻為自己寫一則墓誌銘,我的開頭會這麼寫:

這裡躺著的是一個LUCKY BOY。

如果我現在可以為我的前半生做個小結,我會說,我是幸運的。我是個擁有特權的人。

讀國小的時候,美術老師會特地騎著腳踏車載我去坐小火車,在路途中跟我講藝術的故事。

我是個幸運兒。

高中的時候,美術老師允許我獨佔美術教室,讓我為所欲為。我是個幸運兒。

大學的時候,指導教授在田野行旅中打開了我生命的黑洞。我是個幸運兒。

我更大的幸運是,在日後的創作裡,我被整個社會環境支撐著。也很幸運的一路都有貴人相助。

我的幸運是,當我的生命進入黑暗、憤怒、充滿暴力、破壞力的「起乩少年」時,適逢台灣解嚴,台灣政經處於威權瓦解、原始底層的社會生命力正待釋放時,我的破壞性的創作得以被當時的社會所承接,而在學運、社運之中激發著巨大的創作能量。

我的幸運是,當我失婚,創作與生活、社交能力都退化、癱瘓而整個人動彈不得,陷於憂鬱、沮喪、無助之中時,台灣發生921大地震,各種助人團體、心理諮商湧入災區,諸如「藝術治療」的觀念被大量討論、運用,台灣社會也開始正視「憂鬱症」問題。我走進了團體室與諮商室,我也因此得到啟蒙與救贖,轉入自我探索的心靈塗鴉與書寫。

我的幸運是,當我身為人父,渴望肩負起照顧者的角色時,台灣藝術市場也在此時進入九○年代之後的另一波熱潮,而最夯的就是當代藝術的創作。我得以重新站在舞台上,聚集資源,在更多更多人的鼎力相助之中,攀登生命的高峰,成為一個可以在各方面給予分享與回饋的「富爸爸。」

其實,我曾經在生命的不同階段裡寫了幾次墓誌銘。女兒出生後我就曾經寫下了這篇署名「阿麗侯」的墓誌銘。那是在二○○三年。

鐫刻在墓碑上的名字

我已滿臉鬍渣 親愛的父親卻不曾改口 以他發自丹田強壯的聲音 叫我幼稚

長年病苦的母親總是憂心 叫我小可憐

我以為這是我此生永恆的名字 卻沒有登錄在戶口名簿上 也未曾出現在族譜裡

侯俊明是我身分證上的名字 也是我簽在信用卡上的名字

我記得,當我考得全校第一名時 司令台上喊出來的就是這個名字

二十三歲之後 我以六腳侯氏署名發表作品

島嶼南方大平原上的小村莊 我的出生地 六腳之名卻像是對自我形象的描述

起乩的少年赤腳踩在炙熱的土地上 舞著鯊魚劍戳戮自身

人們睜大眼睛看著 在讚許中帶著嘲諷 叫我大師

當我四十歲開始在院子裡種花之後 就再也沒有人這樣叫我了

在烈日下鋤土 全身黝黑砌築花台 我沒有因此摶得花農之名

畢竟我並沒有栽培出新奇的花卉 我只是把花種活了 但這已經是一項偉大的成就了

我剛滿週歲的女兒在花園裡向我走來 伸直臂膀 叫 爸─爸

在彌留之際 這呼喚令我無法闔眼

—摘自 阿麗侯<米朵元年> 詩集

女兒出生,我意識到那個動物性很強的侯俊明必須死亡,也已經死亡,而寫下墓碑上自己最在意的名字──爸爸。而今,女兒已經上小學了,也已經很會唱歌跳舞、妝扮自己了。

去年,二○○七年,在 <圳鳴四十七自述>、<侯氏八傳>裡我顯然又為自己寫下了不同版本的墓誌銘。

如果可以活到五十歲,我肯定又會寫出差異性極大的另一則墓誌銘。

而那又會是關於那一部分的侯俊明的死亡?

Preface : A Lucky Boy’s Epitaph

by Legend Hou

Perhaps it is part of the healing symptom recently I often cannot help myself to have my eyes brimming with tears while I am driving. So I often park the car by the road and let myself cry out. Either sobbing or howling, or just quietly tear down, I allow tears over my face and wet my clothes.

Internally I know that my tear does not come from healing, but from another body-mind experience of sorrow between life and death. I am standing at another turning point of life.

If I was writing the epitaph for myself now, I would have begun as follows:

Here lied down a LUCKY BOY.

If I could conclude my first half part of life now, I would have said that I was so lucky with privileges.

During my elementary school years, my fine arts teacher would ride me with bicycle to take light rail train as particular favor. On our trip, he would tell me stories of arts. I was indeed a lucky boy.

In my high school years, my fine arts teacher allowed me to solely enjoy the fine arts classroom and I could do whatever I wanted. I was indeed a lucky boy.

During my college years, my advisor opened the black hole in my life in the field survey trips. I was indeed a lucky boy.

My further privilege is that I have been supported by the whole social environment in my art creation all the time. I have been very lucky to meet with those who always give me a hand in my time of need.

My privilege is that the moment my life entered “the psychic youth period” full of darkness, rage, violence and destructive power, it was also the time Taiwan underwent martial law being declared ended and the politics and economics were thus facing the dissolution of power politics while the social life-force from low rank was about to be released. My destructive creation thus was accepted by the society then while student protests and social protests inspired my extensive creative energy.

My privilege is that when I devoiced and thus I lost my capacity of creation, life conduction and social relationship skills to become sad, depressed and helpless, it was also the time Taiwan was attacked by the September 21 Earthquake and later the abundant resources of volunteer groups and professional therapists and consultancy services were brought into the disaster area. Concepts like art healing were extensively discussed and applied. The society began to take melancholia seriously. Then I walked into the group support room and consultant room and thus I was inspired and saved. Later I switched my focus to self-exploring mind scrabbling and free writing.

My privilege is that when I become a father and am eager to take the responsibility as caretakers, the Taiwan art market is reaching another heat wave after 1990s. Among them, the contemporary art is probably the most popular and desirable one. I am able to again step into the stage to reach the zenith of life with more supports and help from others as well as more resources gathered. I become a rich daddy who can share and feedback in many respects.

In fact, I wrote my epitaphs several times in different life stages. After my daughter was born, I once wrote the following epitaph entitled Ali Hou. It was in 2003.

The Name Inscribed on the Tombstone

I already grew full beard and my dear father never changed the childish way he called me, in his strong voice from abdomen; my mother suffering from ills for years always worried about me and called me miserable little thing. I thought those are my permanent names. Somehow they were not registered on the residential registration books and didn’t appear in the pedigree, either.

Legend Hou is the name on my ID as well as the signature for credit cards. I still remember that when I was the lead of campus, I was called to the commanding platform in this name.

After reaching 23 years old, I began to sign my artworks with Hou of Liu-chiao Township. It is a small village in the large southern plain on this island where I was born. Liu-chiao is pronounced with another meaning as six-legged and it became a self-image description: the psychic young man stepping on the boiling hot land with bare foot and stabbing his body with shark sword. People starred at me and called me the master in such praise combining with squibs. When I reached 40 and began to plant flowers in my garden, no one called me like this anymore.

Working with a hoe under the burning sun and building up flower bed, I didn’t gain the recognition as a flower farmer. After all I didn’t grow any extraordinary flowers. I just grew them alive. Somehow this was already such achievement to me.

My daughter just reached one year old walked toward me from the garden with her arms open and said: “Dad-dy.” On the point of death, this calling stops me from closing my eyes.

From Ali Hou, Poetry of the First Year of Mido

When my daughter was born, I realized that the Legend Hou of strong animal nature had to die and already died, upon writing down the name which I cared about the most – Father. Now my daughter is already in her elementary school years. She sings, dances, and dresses herself well.

Last year, in the Confession by Jun-meeng at Age 47 and the Eight Legends of Hou, apparently I wrote different versions of epitaphs for myself.

If I lived till fifty years old, surely I would have written quite different epitaph. Which part it would have been, in terms of the death of Legend Hou?

引

1990~1991年劇場經驗對侯俊明版畫創作的影響

資料統整.撰文 / 陳富珍

「今天我看侯俊明的作品,感到非常羨慕,台灣的東西讓他『瘋肖的舞』,那種自由、那種狂想,對環境的態度和我們那時非常不一樣,這是一種進步。對侯俊明而言,台灣的東西是理所當然的。」

─ 林懷民(雲門舞集創辦人)

「與侯俊明合作『五色羅盤』,第一次看到侯俊明剛出爐的設計圖時,我相當吃驚。因為『刑天』的意象凝練有力,充滿祭儀性和神秘性,深深吸引我。……年輕又具創作狂熱的侯俊明,不斷在設計圖上填滿新的東西,這樣豐沛的創造力是令人羨慕的。」

─ 林秀偉(太古踏舞團負責人)

「侯俊明的創作中傾露著台灣鄉間特質在進入繁雜都市後的扭曲與堅持。而優劇場正期待將台灣本土文化的根扎入劇場的創作,來讓這塊土地的人看看自己土地長出來的樹與花。一種『長一個台灣人自己的樣子』的內在強烈慾求,促使我們共同攜手,並非是為了塑造誰的專業成就,而是為了期盼一個『文化』的出現而合作。」

─劉靜敏(優劇場負責人)

(以上三段文字節錄自雄獅美術247期1991年8月號)

從大學時期發表「工地秀」和「大腸經」的1987年算起,在侯俊明個人藝術創作的歷程中,這20年裡,台灣政經環境經歷了最巨大的時代變遷,藝術浪潮風雲了幾波的翻湧。其中,90年代前後正是台灣小劇場蓬勃發展、生猛活躍、自由狂放的運動期,也是台灣裝置藝術火熱興盛期,兩股力量衝激匯流,撞起了跨界合作及集體創作的風潮,讓台灣藝術迸放出許多精采創造力。

1990~1991年短短兩年之間,侯俊明在小劇場和表演團體的邀約下,以美術工作者的身分參與舞台裝置創作和部分展演活動,分別和五個不同表演團體合作,參與六齣劇場展演活動(如附錄二 P.348),侯俊明曾說那是他的「劇場年」,為侯俊明正式展開藝術創作生涯,非常重要、影響深遠的一段過程,是奠基侯俊明以版畫創作為載體,以常民文化為語彙,以社會議題為反思,以集體創作為手段的「孕育期」。

侯俊明曾在1991年7月出席當時雄獅美術所舉辦【整體藝術在台灣】,在座談會上這樣說到:「參與劇場活動對我的影響可以就幾個層面來看,首先,我覺得台灣的小劇場相對於許多美術界的朋友而言,他們是我所接觸過最能敏銳感知週遭環境訊息的一群人。他們帶給我的最大刺激:一方面在於從個人單向的創作,導向群體的、未知的整體藝術經驗;另一方面則是將自己從絕緣的純粹美學體系,甚至是一種狹隘的慣性視覺形式的沉溺裡解放出來,進入一個更廣泛的人文視野。例如「環墟劇場」、「河左岸劇場」對台灣史的閱讀與挖掘,「優劇場」、「零場」對車鼓陣等民俗藝能的學習與轉化,對我在創作的方向上都有很大的啟發。因而除了「二號公寓」與「台灣檔案室」1 之外,劇場成為我離開學院之後,一個很重要的學習據點。至於在實務工作上,燈光、演員的走位及他們與空間的關係,使得我再回來面對美術作品時,對作品所處的空間氛圍有了更周延的考量,甚至在材質的選擇使用上也是。???我相信這些功課在日後也必將深潛、幻化為我個人各式各樣的創作。或許可以這麼說吧,我是很貪婪的吸吮著劇場所能提供的任何資源。」

從侯俊明的這段話中,即可以理解到,在1987年台灣政治解嚴之後,整個社會民間力量被釋放出來,自由開放的氛圍瀰漫,許多原屬禁忌的本土論述得以被公開,成為文化再生共有的豐沛資源。而當時標榜著反體制的台北小劇場團體,正扮演著極重要的喚醒與催化的作用,許多劇團或地下劇場不再被動地接受既定的規範及教條,積極主動地爭取屬於自己的表演空間,嘗試突破現況。小劇場不斷以其生率而猛烈的行動力,比其他類型藝術表現作更直接、積極地衝擊著當時崩解中的台北政經體制。

劇場反動的理念不僅落實在表演主題內容的訴求上,如政治議題、社會議題、環保議題,關懷弱勢族群等,有些劇場極力突破巢臼,標新主張,表現形式有著截然不同以往的展演方式,他們引用西方「後現代主義」的概念,展現反敘述、拼貼、剪接等新穎的劇場方法,前衛、創新、實驗性格十分強烈。部分劇團開始走上街頭,投入政治運動和社會運動,以「行動劇」直接參與街頭抗爭,還有部分劇團則朝著「整體藝術」方向發展,以跨界跨領域的合作模式,企圖發展出別具新意的作品和文化展演樣貌,台北小劇場的活蹦奔放,目不暇給的演出打破了既有的劇場框架,在這樣的時空環境下,讓跨界參與其中的藝術工作者有了更多的揮灑空間和表現舞台。

侯俊明在1991年曾說到:我對整體藝術的鍾情,可以說是被「環墟劇場」、「優劇場」、「太古踏舞團」及其他劇場朋友給「寵」出來的。他們把空間讓出來,並且期待我在裡頭迸發出獨特的創造力,來與之碰撞,以發展出有別於傳統的表演藝術,我以美術工作者的身分被邀請參與創作,因此「美術」或者說「裝置藝術」,在這些合作的作品裡充分被尊重著,保有它的主體性,並展現視覺藝術特有的張力與魅力。

1987年,侯俊明在大學時期發表了「工地秀」、「大腸經」兩件頗具爭議性、反叛性和社會性的作品,即受到藝術圈不小的關注,1989年服完兵役退伍回到台北之後,接獲劇團的邀約,開始了參與舞台裝置創作和展演活動。

侯俊明參與舞台裝置的處女作,是1990年和環墟劇場的導演許乃威、團長李永萍合作,擔任劇名為「暴力之風」的舞台美術設計,這是台灣劇場有史以來第一齣以「二二八」歷史事件和省籍問題為題材的戲劇演出,觸碰了長久以來的歷史禁忌話題。為了能更深入了解這齣戲的歷史背景,以創作出能傳達戲劇精神的舞台裝置,侯俊明加深了對台灣史的閱讀和挖掘。

這齣戲在台北國家劇院實驗劇場和香港藝術中心兩地演出,侯俊明再度變化了「刑天」的意象,在「暴力之風」中展現另一種歷史悲情的圖像,這個圖像後來發展為版畫作品「搜神記」中的「刑天」。

同年,侯俊明也與太古踏舞團林秀偉合作「五色羅盤」,這支舞碼為林秀偉創作的個人獨舞,用舞蹈肢體表演來傳達生老病死的生命歷程。侯俊明曾說:與林秀偉合作「五色羅盤」是一次蠻過癮的經驗,一來一往的互動,使作品成為有機的生長,林秀偉在基本創作理念的掌握下,常能機動的隨新做出的劇場裝置空間,作進一步的發展,調整她的舞蹈結構,另一方面我也在一次又一次的觀看排舞過程裡,一再的被刺激而凝塑著舞台上可與之對話的圖像和材質。林秀偉也曾說:侯俊明年輕、狂熱的創作慾望太強烈了,以致常常不斷地發展新東西將舞台填滿,然後,她得再和他溝通刪減東西,她在合作的過程中,看到了侯俊明旺盛的創造力。

在「五色羅盤」的舞台裝置上,侯俊明以鐵板做出剪影的造型,使圖像在燈光反射下具有版畫效果,這個發想的概念,一部分來自1988年雲門舞集演出「我的鄉愁?我的歌」時的舞台佈景設計,即是以奚淞的一幅版畫「冬日的海濱」為靈感發源。不同媒材的創作在不同的藝術場域中相互演繹作用的觀念,在侯俊明的創作思維裡開始萌發,「五色羅盤」舞台裝置的創作經驗,為侯俊明發展版畫創作敲起了意念。

同年,優劇場「傳奇人物」陳明才編導的年度大戲「七彩溪水落地掃」,同樣找上侯俊明參與服裝、道具的美術設計。這齣戲的內容在當年節目傳單上的摘要說明如下:傳說古早以前,現今台灣海峽飛來一隻黑龍精興風作浪,雲遊四海的奇異老人決心為民除害,展開生死鬥,打敗黑龍精,鎖在海底,黑龍精不時想偷跑,使得海面暗潮洶湧,討海人稱這片海域為「黑水溝」。渡黑水溝來台的祖先,辛苦建立家園,數百年後,這隻黑龍精因鐵鍊生鏽衝出海底到黑龍村,黑龍村是一處偏僻庄頭,黑龍精要求村民為他蓋廟(工廠),他許諾將保佑村民賺大錢。黑龍精能吃能放,排泄物四散,毒死村民小孩,使得農作物無法成長,溪水變成七彩色,魚蝦大量死亡,村民身體也嚴重病變,村民集體向台北來的大官虎投訴,卻被警察強制驅離。村民無奈決定自力救濟和黑龍精展開大決戰,他們將龍的排泄物做成祭品,在黑龍精誕辰獻給牠食用,讓黑龍精自食惡果中劇毒。

《七彩溪水落地掃》的「七彩溪水」所指的不是七彩絢麗的溪河,是一種反諷,暗指台灣的溪流,如基隆河、淡水河、雲林北港溪、台南將軍溪、高雄後勁溪…等這些當年因遭工業污染,變成七彩雜陳、又臭又毒的水溝。而「落地掃」所指的是台灣早期民間戲曲藝術(如歌仔戲)的表演形式,不在舞台上演出而是直接在空地上表演,或者遊街時沿路表演。所以,這齣戲並不在室內劇院演出,而是以「落地掃」的野台戲形式,在全台灣15個廟口和戶外廣場巡演。

因為參與《七彩溪水落地掃》的全台巡演,侯俊明常常騎著摩托車跑台灣廟會,也因而接觸了更多的台灣民俗文化和常民活動,因此對侯俊明而言,參與《七彩溪水落地掃》的工作,最重要的影響,不在美術設計作品的表現上,而是這經驗又一次重重地讓侯俊明對草根力量、本土意識與俗民文化思想起撞擊。

侯俊明曾說:雖然從小在嘉義六腳鄉下成長,但所有教育的過程,都被灌輸、鼓勵都會文化的優越性和高尚感,與自身生活的鄉土關係和文化認同是被切斷的,直到大學讀書時期,在陳傳興教授的帶領下,開始在台灣鄉野四處旅行,進行田野調查和民俗活動觀看,才受了啟蒙,對這些原生草莽性格強烈的民俗文化有種被喚醒的覺察,但這些訊息都還在一種內化整理狀態。《七彩溪水落地掃》的經驗是更為直接強烈的又一次衝擊。那時,為了做這齣戲,和劇場的成員曾經多次到實地對被污染的河川環境進行田野調查,同時間,優劇場的負責人劉靜敏也開始推動尋找「台灣人的身體」的活動,這些內外因素一一觸發自己對台灣這片土生土長的地方和未來的藝術創作方向,作更深一層的思考。

幾年的鄉野活動下來,面對文化深層結構和生命底層中接近原始狀態的本能、慾望及恐懼,這些扎根於生活的民俗圖像與地方藝能的學習和轉化,所看、所感、所思解構了習於知識辨證和美學理論的侯俊明,對他投入版畫創作形式和內容取材,著實有著關鍵性的影響。

參與劇場運動,帶給侯俊明的,不僅只是配合表演內容或舞台效果的裝置創作,而是更深刻的整體藝術生命思維與面對。所以侯俊明曾說:整體藝術可以從兩個層面來談:一是不同媒體創作者在整體表演裡的互動關係;一是它本身就是一個創作的類型〈另一類藝術〉,它所牽涉到的或許不見得是對媒體互動的思考,而可能是「藝術與非藝術」、「藝術與生活」、「藝術家與觀眾」等關係的一種挑釁和質問,它可能仍為單純的個人工作,並只使用極簡的媒體與形式。透過一種接合、結合而「發生」為整體藝術,或許仍保有個別創作媒體的特質與形式,舞蹈不單純是舞蹈、戲劇不純然是戲劇。總的來說,它什麼都有,卻什麼都不是。但在「前衛」精神的導引下,不管是顛覆或革命,都顯露著生機無限的反叛性格,並不斷地否定與跳脫,始終保持著它的「邊際性」。

因著這個「前衛」精神的導引與保持「邊際性」的企圖,侯俊明在1990年和一群朋友包括肢體表演者、音像實驗者、文字工作者和美術工作者,聚合成立「泛色會」,將團體定位為「總體藝術團體」,1991年初在由藝術家黃銘哲經營的台北尊嚴藝術空間發表第一個作品「拖地紅─侯府喜事」,這個無人現場表演時是個空間裝置藝術,有演員現場表演時是另類戲劇的總體藝術作品,是以侯俊明個人情感挫折為原始動機,衍發出來的裝置展演新形式的嘗試,跨領域集體創作的另一種實驗,陳述婚禮與喪禮、新郎和新娘性別的錯置。被侯俊明視為個人重要生命儀式作品的三部曲之一2 ,其裝置圖像後來也發展為「搜神記」版畫中的「拖地紅」。

「拖地紅─侯府喜事」這件〈或這齣〉以侯俊明主導的展演裝置作品,在當時評價兩極,藝評家黃海鳴在當年曾撰文寫到:「在拖地紅作品中,表演團體乃試圖將肢體、音樂至放回平等地位,獨立發展為自主軸,相互依存,互為主從,建構一個放射狀,甚至是多元、多焦點的『整體藝術』。就內容而言:作品直指人性最深的慾念,並混雜對禁忌,對權威的顛覆。」

侯俊明也曾對這個創作有過一段談話,他說:「想傳達的除了在內容上想對性愛主題提出我們的觀點之外,最重要的是,我們希望在方法上找尋不同領域的創作者之間比較理想的結合狀態,其間彼此互為主從,並且每個人很本位地從他自己內部的表現慾求出發,說他自己真切要談的話,並用他最契合的形式,去傳達個人最私密的經驗,尤其是關於性愛的論述。」不過,這個極具實驗性的創作,因創作經費有限,使得經濟條件不寬裕的「泛色會」成員非常辛苦,以致不久團體即宣告解散。

但從侯俊明的談話中,可以看出他對跨領域集體創作的一種期待和希望,在開放的整體藝術裡,他並不擔心各種異質事件、元素的介入而導致結構或秩序的被破壞,相反的,他期待一種相互的顛覆關係。在迎合異質力量與自我保存之間拉扯,並在其中取得平衡。所以,侯俊明曾說:「整體藝術進行的其實就是一場各自能量的釋放與互相吸納的過程。我自己就像個海綿,要把合作者傾注而來的資源,不著痕跡的吸納著,吸進來的可能是水,但再擠壓出來的可能是「血」—我體內奔流而出的「血」。」

吸納與釋放之間,對才剛開始真正投入藝術創作的侯俊明而言,都是一種能量的積累和開展。1991年,侯俊明第二度和優劇場合作,劉靜敏編導「老虎進士」於國家劇院演出,表演的故事內容敘述一位在科舉考試時代因求取功名不得志的知識份子,於人生失意之際,遂變身吃人老虎,傷害他人。侯俊明認為:這是一齣深具古典文學意涵的戲劇,給他帶來的是文學性的啟發。之後,為這齣戲作的舞台裝置圖像也轉為單張版畫。

同樣在1991年,侯俊明參與的另一個表演藝術經驗,則是由舞蹈家李麗珍帶領的「無垢舞團」於國家劇院演出「台灣原住民舞樂系列─布農篇」,侯俊明在其中扮演的角色並非美術設計工作者,而是擔任舞台助理,對他來說,最重要的意義是,因為這是一齣傳達關於土地與文化的布農族樂舞,讓他有機會到山上部落參與田野調查研究,深入原住民本土文化與祭典、儀式,也在其中累積更豐富的集體創作經驗。

回看參與劇場展演活動的過程,侯俊明曾說:他和每個團體的合作關係,狀況都不一樣,也分別出現不同的問題,但對這些問題的思考與解決,卻對他整體藝術創作的形成有極大的啟發。

從1992年發表第一套版畫作品「極樂圖懺」,到2008年這十六年,侯俊明共創作了十套版畫作品,和數十件單張版畫作品,如果沒有劇場展演運動的洗禮,侯俊明的創作思維是否會如此敏感於環境事件和社會議題?藝術表現媒材是否會選擇如此具民俗意象的版畫形式?答案不得而知。但可以確知的是,正因為參與劇場展演運動,吸取了跨界合作共同創作的不同量能,改變了純視覺藝術封閉的狹隘貫性,擴張了人文視野與思考向度,讓侯俊明的版畫作品,在台灣當代藝術上如此獨特而鮮明。

註1. 「二號公寓」與「台灣檔案室」為侯俊明在90年代參加的兩個新生代藝術團體。「二號公寓」成立於1989年8月,被視為台灣藝術展覽替代空間的鼻祖。當初由蕭台興提供師大小巷內閒置公寓房子作為團體會員展覽和討論空間。由會員輪流每月一檔展覽。當時活動力極強,對台灣藝壇生態影響不小,成員包括:蕭台興、范姜明道、連誠德、李美蓉、林珮淳、、侯俊明等20多人。該團體於1994年8月宣布解散。「台灣檔案室」則成立於1990年4月,主要成員為連誠德、吳瑪俐、張正仁、侯俊明等人。當年5月20日舉辦一次策劃性聯展,主題為「慶祝第八任總統就職典禮藝術聯展」,針對台灣政治、社會與文化現象作深刻的批判、反省與諷刺。

註2. 侯俊明視為個人重要生命儀式作品三部曲為:第一部「侯氏神話─刑天?密馬解毒」(1990);第二部「侯府喜事─拖地紅」(1991);第三部「以腹行走─36歲求愛遺書」(2000)

Preface : The Influence of Theatre Experience 1990~1991 on Hou’s Prints

Information compiled and written by Jane Chen

Ever since his first announcement of Property Site Show and The Intestine Mantra in 1987, when Hou was still in college, it has been twenty years of Hou’s creation career. During this period of time, Taiwan has undergone the most dramatic change politically and socially while local art circle also witnessed several agitating movements. Early 1990s is the moment when avant-garde theatres develop vigorously while Taiwanese installation art grew flourishingly. The two trends merged and confronted each other into a new trend of cross-collaborations and collective creations, which brought out such wonderful creativity on Taiwanese art.

During the two years from 1990 to 1991, Hou was invited by many avant-garde theatres and performance groups to participate in stage design and partial performance as a visual artist. He worked with 5 performance groups for 6 productions (See Appendix II P.350). Hou once said that period as his “theatre years.” This experience becomes very influential and essential for Hou to formally begin his art creation career. This is also the fundamental period for Hou to choose print as his medium, folk culture as his language, social issues as his topics, and collective creation as his approach.

When Hou attended the Holistic Art at Taiwan Forum held by Lion Art in July 1991, he said: “There are several aspects regarding the influence from theatre events to me. First, avant-garde theatre circle is one of the most sensitive with surroundings, compared to many my peer colleagues from visual art circle. They bring me such stimulation; on one hand, they guide me from personal one-way creation toward collective and yet unknown holistic art experience; on the other hand, I was released from the ivory towel of pure fine art system, or even a narrow and habitual visual addition , and guided into a wide-open humanity vision. For example, the further reading and discovery of Taiwan history by Ruin Circle Theatre and Left Bank Theatre, and the studying and transfiguration of folk art by U Theatre and Zero Theatre are very essentially inspiring to defining my creation direction. Theatre becomes one of the most important learning resources other than Apartment No. 2 and Taiwan Documents Cell. As to practical aspect, lighting, walk-through rehearsal and the relation between actors and space, make me have more holistic consideration on the space and aura of artworks. It is the same case on my choice of material…I belief that those experiences will further become the sources of my personal recreation. Put it in this way, I am very greedily absorbing all sources that theatre could provide to me.”

From his statement as above, it is understandable that after the political martial law-lifting in 1987, the whole social power was released. An aura of freedom and openness was spread and many local discourses which was taboo before were able to be published, in which became the abundant resource for the cultural rebirth and sharing. Many avant-garde theatres which claimed to be antiestablishment in Taipei played a very important role as rousers and catalysts. Many avant-garde theatres and underground theatres no longer passively accepted existing rules or dogmas and instead, aggressively and actively fought for their own performance spaces and intended to break out through current circumstances. The raw and fierce action of avant-garde theatres directly and seriously impacted the disordering Taipei political and economic systems then, compared to other types of art forms.

In 1987, Hou announced his two highly controversial, rebel and social-issue-oriented pieces: Property Site Show and The Intestine Mantra. Even though he was still a college student, the art circle already grew strong attention on him. In 1989, upon finishing military service and returning to Taipei, Hou was invited by theatres to start stage design and installation project, as well as display and performance.

Hou’s first stage installation piece is Wind of Violence in 1990. He worked as stage art designer with Nai-wei Hsu, the director, and Yun-ping Li, creator of Ruin Circle Theatre. This drama is the first one whose theme touches the February 28 Massacre and ethnic group issue, a long-forbidden taboo. In order to further understand the historical background of this drama and create best expressive stage installation, Hou hence conducted further reading and research on Taiwan history.

This drama piece is performed at Experimental Theatre of National Opera Hall, Taipei and Hong Kong Arts Center respectively. Later on, Hou again transfigures the metaphor of Hsing-tien and shows another image of historical tragedy in Wind of Violence. This image became the new Hsing-tien in Hou’s print series, Anecdotes about Spirits and Immortals.

The same year, Hou worked with Sui-wei Lin and Taigutales Dance Company for the production of Five-Color Compass. This is a solo choreography piece by Lin in order to express a life journey from birth to death with human body language. On the stage installation of Five-Color Compass, Hou used iron plate to create cut-out form and thus those images looked like print works under the light reflection. Part of this particular inspiration came from the stage design of Cloud Gate Dance Company for its 1988 piece My Nostalgia and My Songs, which was inspired by Hsi Song’s print work Seashore of Winter Time. The concept of adopting different materials for different artistic space and cross-interpretation began to root inside Hou’s creation thinking. The stage installation creation experience of Five-Color Compass became a development trigger of Hou’s print works.

Again in 1990, Hou was invited to participate in art design for costume and props for U Theatre and the legendary Ming-Tsai Chen for their annual performance The Road Show of the Story of Rainbow River. The story is summarized based on its program then as below: Long time ago, a black dragon came to stay at the now Taiwan Strait and it caused a lot of trouble and disasters. A wondering master decided to get rid of this monster for local people. The master and the black dragon thus had fierce fight and eventually the master beat off this monster and locked it deep in the ocean. The black dragon always tried to escape and thus made the ocean very wavy. Fishermen called this marine area “the Black Straits.” People came cross this black straits and build new home here. Several hundred years later, this black dragon broke the oxidized iron chain and got out of ocean. It came to a remote village called Black Dragon Village. This monster demanded village residents set up a temple (implying a factory) for it and it promised to bring them good fortune as return. The black dragon thus stayed in the village. It ate a lot and thus excreted a lot. Its ordure was so poisonous that not only children of the village died, but also crops could not grow. The river became a color of rainbow and fishes and shrimps died. Later on villagers got sick and they went to plead to federal officers from Taipei City. However, those villagers were forced to leave by the police. Finally those villagers were forced to fix this problem by themselves and they decided to fight with this Black Dragon: They made ceremony offering food with the dragon’s poisonous ordure and they had dragon eat the food on its birthday ceremony. The monster died at its own poison.

Because his participating with the traveling performance, Hou often rode his motorcycle visiting temple fairs and thus he encountered with many Taiwan folk culture and folk events. For Hou, the major influence from working at the Road Show of Story of Rainbow River was not about the presentation of fine art design; rather such experience heavily impacted onto Hou’s viewpoint toward grassroots power, nativism and folk culture and values.

Hou formed Multi-Color Society with his friends from performers, audio-image experimenters, writers and visual artists in 1990. The group positioned themselves as “holistic art group.” In early 1991, Hou presented the first artworks of this group, The Wedding of Hou’s Family- Red on the Ground at The Dignity of Taipei Art Space run by artist Ming-che Huang. This piece can be appreciated in two ways: without actors on site, it is a site-specific installation while actor performing on site, it becomes a holistic artworks with alternative theatre performance. This piece is inspired by Hou’s personal emotional frustration and further developed into a trial of new form combining installation and performance. It is also another experiment of cross-field collective collaboration creating which describes the wrongly-matching between wedding and funeral, broom and bride. This piece is regarded by Hou himself as one part of the trilogy of his important personal life rituals. The installation image later is developed as Red on the Ground in his print series Anecdotes about Spirits and Immortals.

In 1991, Hou collaborated with U Theatre again. The Tiger Scholar edited and directed by Jingmin Liu was performed at National Opera Hall. The story describes an intellectual of imperial examination period failed to gain his position became a tiger to hurt others and eat others while he fell into difficult time. Hou thought this drama piece a theatre piece of classical literature contexts and it brought him literal inspiration. The stage installation later is developed into individual print work.

Once again in 1991, Hou participated in another performance art experience. The Taiwan Aborigines Dance and Music Series- the Bunun was performed by Legend Lin Dance Company directed by dancer Li-jean Li at National Opera Hall. Hou was not art designer but a stage assistant. For him, this is a Bunun’s music and dance piece relating to land and culture and thus he has opportunity to visit tribes of hills for field survey. He has further understanding and more knowledge regarding aborigines’ culture, ceremonies and rituals. He also gains more collective creation experience.

When looking back to his participating process of theater display and performance, Hou said that his collaboration with each performance group was individual case. Each project had different problems. However, to think and fix those problems is great inspiration toward his development on holistic art.

Since his first print series of Erotic Paradise in 1992, it has been 15 years by 2007. During this period of time, Hou creates 10 print works series and many individual print works. Would Hou’s creation be so sensitive toward environmental and social issues, without his theatre movement experiences? Would he choose the art expression medium of print that possesses strong folk texts? We probably won’t have the answer. One thing we know for sure is that Hou’s participation of theatre movement made him absorb versatile energy of cross-filed collective collaboration and it changes the customary narrowness of pure visual arts. It also enlarges Hou’s humanity vision and thinking dimension. All of those make Hou’s print works such unique and stand-out in Taiwan contemporary art history.

|

|

|

書

評

|

|

|

|

|